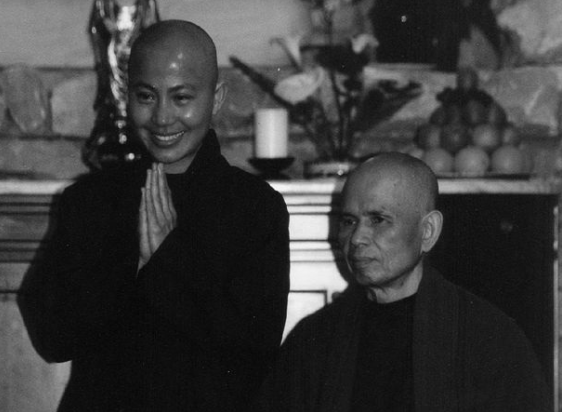

In 2008, after eight years as a nun, I received the Dharma Lamp Transmission along with other monastics in the plumeria and camellia ordination families and with some lay practitioners. In this ceremony, Thay gave each of us a Transmission Gatha in the spirit of the heart-to-heart transmission, so that we may carry on the light of the Buddha and of Thay. This ceremony also officially made us Dharma teachers, able to teach the Buddha’s teachings to others. However, I was fully aware that Thay continually offered to all of us, his monastic and lay disciples, the Lamp Transmission through his Dharma talks and through the living Dharma of his mindful speech and bodily actions.

Part of this ceremony required that I compose a short poem, a gatha, to offer to my teacher and the community. This was my insight gatha:

A flower bud falls, a thousand trees continue.

The music is fading, birds sing out of space.

The mind of love shines in the sea of fire.

Together with the old moon, the vow goes forward.

I have seen a flower bud falling many times. But one time, as I was walking slowly to the Ocean of Peace meditation hall in Deer Park and passing by an oleander grove, I saw a white oleander flower bud fall to the ground. It shook me deeply to the core. I realized, “Oh, a flower does not have to wither to fall to the ground. It can fall while it’s still a bud, having just blossomed, in perfect bloom, or while it’s withered on the branch. It takes just one more condition—maybe a gentle breeze or the weight of an insect—to make it fall to the ground.

Somehow I can understand and accept that there are those I love who died very young. Now each time despair arises in me, the image of that flower bud also arises, and I no longer despair as I used to. Gradually, I was able to see that a falling flower bud has one thousand trees to continue it.

When we love someone, it’s not because we live next to the person that we love him or her. We love because we can see the beauty in that person, and we learn to love him in a way that he lives inside us. We can see the suffering and shortcomings not yet transformed in that person, and we practice wholeheartedly in order to help transform those things for him. That is true love. We can continue that person. Whether that person is still alive and near us, or whether his body has already disintegrated, he is always in us—we are one, and not two separate entities anymore.

There are love stories that come to an end; love arrives so beautifully, and then it fades away. However, in the Buddhist spirit of love, there are songs that will never end. There are moments when sitting still with the Sangha, I feel so happy. I see that I lack nothing. Everything and everyone that I thought I had lost is still with me. Those moments are still and complete. The song rises, and it transcends time and space. Sitting still is one of the greatest happinesses in my life of practice.

I sense that the trials of my life are not over. In every cell of my body, I am carrying the undercurrents of countless generations of ancestors. I carry them, I practice accepting them, and I practice patience with them.

Sometimes we promise this with one person and that with another person. My monastic vows are different. They have come to me from my ancestors. When I was in medical school, there were times I yearned to walk very slowly. Instead of taking the elevator, I walked up the stairs very slowly and quietly. Doctors who were running up and down the stairs would be startled when they suddenly saw me. Some walked slower, because they saw me doing so.

There were so many times in my life when I also wished to be silent. Once I told a good friend that I wished I could remain silent for one month, without having to say anything. My friend laughed and replied, “You’re a medical student. You have to take care of patients. If you don’t talk for a month, then who will take care of them? Who will visit them? Who will give reports on them?”

Since I became a nun, I understand that deep inside me were these old vows that I longed for but could not articulate. I didn’t know how to get in touch with them, and I didn’t know how to make use of them to help me find a way out. Once I had the chance to come home to myself through the practice, I realized that they had always been real in me.

Just a few days ago, I looked at myself in the mirror. I had been sick. Often when I look in the mirror I just see the scars on my forehead and the discolored patches on my nose. But that morning, an inner question arose: “Can you see the eyes of your grandmother? Can you see the mouth of your mother? Can you see the body of your father?”

Once a college student asked me, “What is most important to you?” “My awareness,” I replied. Without awareness, I would not know what I have and what I need to transform and heal.

I no longer cry bitterly or suffer as I did during my first years at Plum Village. I often invite John to practice with me. When the alarm clock rings in the morning, I turn it off and at the same time I say, “Thank you, John, for waking me up to this wonderful life.” John used this clock for years when he was alive. While doing walking meditation, I say, “Old days and one thousand years in the future come home on the same path.” When I miss the familiar image of my friend, I tell myself, “I don’t need to look for you anywhere far away. You’re right here inside me, in every breath and every step. Dear John, I have come home.”

i once was a river

I once was a river, a river falling in love with a cloud and chasing after it. When the cloud disintegrated, I experienced excruciating pain. The pain was so deep because I thought the cloud would always be there, and because I had neglected it at times. I know now that if I were to love my teacher in the way I loved the cloud, if I were to love my practice and nun’s robe in the way I loved that cloud, then even while they are still here with me, I will already have lost them.

One day, the cloud will disintegrate, and I will return to my two empty hands. So I practice wholeheartedly, coming back to my breathing, coming back to my steps, and being present for what is in me and around me.

I recently saw a video of Thay with some monks and nuns. It had been filmed right after I’d come to Plum Village. The camera was pointed at the stage and showed the back of my upper body as I sat in the audience. My hair was pulled together in a bundle; I hadn’t realized it was so full and black. It reflected the light which shone in a semicircle around the bundle. I was wearing the brown robe of an aspirant, a nun to be. Who is that person whose hair is now completely shaven? Am I different from her? What has she gone through? I saw the monastic sisters onstage. One looked just like me. I’d previously wondered, “How can someone else look like me? How can people mistake me for another monastic sister?” However, in that moment I saw how I could mistake that sister for me. I also saw my face in the face of a Korean sister, in a fifteen-year-old sister, in a French sister, in short or tall, thin or chubby sisters. I saw sadness. I saw faith. I saw a smile of pure joy. I saw restlessness. I saw my face in their faces, looking at them, being them.

My inner eyes tell me that I no longer need to hide myself in shame or to show myself in pride. I have never been alone. My face is the face of my sisters, of my partners, of my mother, of my grandmother, of leaves, of mountains, of memories, and of awakened moments.

Feather at Midday

If I had not stopped to watch

a feather flying by,

I would not have seen its landing—

a tiny pure white feather.

Gently, I blew a soft breath

to send it back to the spring.

If I had not looked up to watch

the feather gliding over the roof,

I would not have seen

the crescent moon hanging at midday.

Spring 2001

—Sister Dang Nghiem

(The above is an excerpt from: Sister Dang Nghiem: Healing, Parallax Press 2010)